A twitter-brief summary of the Chaos Theory of Careers.

This blog is a companion piece to a blog on using the Chaos Theory of Careers Practically in Counselling. That blog will appear in time on David Winter’s Careers in Theory Blog (http://careersintheory.wordpress.com/). Specifically find the article here http://wp.me/pCwmV-oI #careersintheory Below I set out “briefly(!)” some of the key ideas in the Chaos Theory of Careers. It may help you better understand my methodology in the Chaos Counselling blog.

The Chaos Theory of Careers (CTC) (e.g. Pryor & Bright, 2003ab, 2007, 2010; Bright & Pryor, 2005, 2007) states that people are complex dynamical open systems and as a result they are subject to:

Complexity;

Change;

Chance

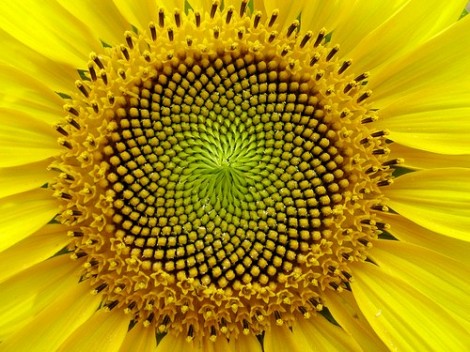

One property of complex dynamical systems is that under certain conditions, relatively stable patterns emerge from the interaction of all the complex influences and changes. In chaos theory these patterns are called Fractals. They exhibit symmetry over time and scale, which means that self-similar patterns emerge over time and self-similar patterns can be seen at every level as we investigate deeper and deeper into the patterns. The classic example in nature that people use is to consider the coast line of a bay. At one level it appears as a large sweeping bay, but if we get closer we observe smaller inlets that resemble the larger bay, and we can keep going right down to small rock pools and see a similar patterns of ever decreasing little bays. That is self-symmetry over scale.

Another feature of these emergent self-similar fractal patterns is that while they are reasonably stable, they are continually changing and sometimes this change is dramatic and is big enough to reconfigure the whole pattern and indeed the system from which the pattern emerges. To continue with the example of the coast line, we can see this happening in nature. Over time the coast line is formed by the eroding effects of sea and wind (and people!). Generally this change is gradual or even imperceptible. However occasionally they are rock falls, landslides, floods or droughts. As I write this, an Earthquake has just struck in Christchurch, New Zealand another example of dramatic change. The result of such influences can be a dramatically reconfigured coast line.

So fractal patterns are we what we would call dynamically stable – continually changing but generally in a self-similar pattern, but subject to occasional dramatic and unpredictable changes. Further these fractal patterns are not simple or easily captured or described by conventional methods.

Excercise

Try this exercise. Look around your room and identify a triangle, a square and a circle. The likelihood is that all the exemplars of these shapes will have been man-made. Now take a look out of the window, and search for patterns that a lot more complex, but kind of self-similar. You might see clouds, or trees, or grass, or even the waves on a sea. All of these things have a pattern, a shape, and all these patterns have a “sort of like old” repeating aspect to them. They are all living and moving – the are all dynamic. They are all natural and not man made.

This is an important insight, because those man-made objects you identified – the triangles, circles and squares are man-made (Platonic) forms. They do not exist precisely in nature no matter how much Plato wished they did. Nature is more complex or messy if you will.

However that has not stopped us from trying to get nature to conform to our simpler approximations. So clouds are roughly elliptical, mountains are roughly triangular etc. But in reality as Benoit Mandelbrot (1975) (the man who invented fractals) points out “clouds are not ellipses” – they are more complex and that complexity matters. In very much the same way, how often do we object to being reduced to a simple stereotype or “put into a box”.

So I hope you can see that within the Chaos Theory of Careers we are going to emphasise concepts like complexity of influences, dynamic change, unpredictability and emerging complex (fractal) patterns. These terms are going be to our lingua franca –

Change,

Chance,

Complexity,

Fractal patterns,

Emergence.

To that we need to add a couple more concepts if we are going to equip you will all the new language, because one of the Benefits of the Chaos Theory of Careers is that it offers processes to understand change and how people react to it, whereas more general systems approaches have tended to be good at highlighting a range of influences we must consider, but relatively silent on how these operate and how systems behave in stable and unstable modes.

The first of the additional terms is non-linearity. Simply put consider this. Imagine you had three standard bags of sugar and some kitchen scales. Every time you put a bag of sugar on a set of kitchen scales, the weight displayed goes up by the same amount. Add a bag, add a kilo. It is a simple linear relationship because we could draw a graph where we had number of the bags of the horizontal scale, and weight on the vertical scale. Plotting the graph would give you a straight line.

In a non linear situation, imagine you had three objects: a bag a of sugar, a pillow and a piece of lead the size of a paperback book. This time as you add the sugar, we get the 1 kg increase, then we add a large bulky pillow and the weight goes up about 0.5 kilo. So the straight line graph dips abit. Then we add the smallest object, the lead book, and the weight goes through the roof. Indeed we break our scales and run and hide from mummy. That is a non linear relationship and they are very naughty boys indeed. They are naughty because they make predictions very hard if not impossible to make. If really big things likes pillows can have small effects and really small things like lead paperbacks (a lead paperback is one full of leaden prose!) have huge effects, then we can’t extrapolate a neat straight line that tells us what is going to happen next.

In the CTC, non-linear relationships are the norm, not the exception. Such small things can have profound effects on a career – for instance being two minutes late to an important meeting can result in you being fired for lateness, or avoiding being assigned to a project that ultimately fails, thus ensuring you avoid being fired.

Finally, it is useful to consider how these complex dynamical systems hold themselves together – what limits them, constrains them? This is where the idea of an Attractor comes into play. For an extended consideration of these see David’s early Careers in theory blog entry and my commentary on his! However here is a quick recap.

Lets ask the question – what limits a system? All systems are limited because if they had no limits they wouldn’t be a system and couldn’t be distinguished from everything else.

The Point Attractor.

Lets a take a really simple system like water emptying out of a sink. Where does the water go? (To Kevin Costner’s waterworld?) It all goes down the plug hole. So we can say this system is made up of the water and the plug hole. As the long as there is water in the sink, we have a dynamic system that operates in a very predictable way. The water all ends up passing through a point called the the plug hole. We can say that we are witnessing a Point Attractor at work. The plug hole works to “attract” the water through it. In a very real sense the plug hole makes the system behave in a very specific way. The system cannot operate in any other way unless of course we change the system by adding things, like blocking the hole, or adding other holes in different places etc.

So Point Attractors are in operation when a system is limited to move only towards a clearly defined point.

The Pendulum / Periodic Attractor

A motorised pendulum is a system where the pendulum swings back and forth between two defined extremities. The system is totally predictable like the Point Attractor system because we always know what is going to happen next. Wherever the pendulum is in its swing, we know where it will go next. A pendulum attractor is in operation at those ghastly conference dinners when the people at each table are served alternatively fish or chicken. (I always end up with the one I don’t want and nobody will swop with me!!).

Pendulum Attractors are in operation when a system is limited to move only in between two clearly defined points.

The Torus Attractor

Imagine a weekly family menu as a system. On Monday we have Chicken Tikka, Tuesday is Lasagne, Wednesday we have Stir Fry, Thursday we have Salad, Friday we have Fish and chips, Saturday we have Pad Thai, Sunday we have Roast Beef, then Monday we have Chicken Tikka, Tuesday we have Lasagne, and by Wednesday we die of boredom…

What we have here is a perfectly predictable system that moves between seven different points (days of the week). The system is so predictable that if we are eating Salad, we know what dinners are in store for us tomorrow, the day after, indeed until we ingest our final calorie in life. Other examples of Torus attractors are rules or policies at work or adages like everything in its place and a place for everything.

Torus Attractors are in operation when a system moves through a series of clearly defined points that repeat over time.

Now at this stage we have described three increasingly complex types of system. Have you noticed that all these systems are completely predictable – we can know precisely what they will do next. Have you also noticed that these are all closed systems – i.e. These systems do not allow any external influences or factors to change their behaviour.

In fact such systems are very hard to sustain over time, because other factors inevitably impinge on the best regulated systems. Roots, food or fat block up our drains and plug holes stopping the action of the Point Attractor. Vegans bugger up the simplicity of fish or chicken at the conference dinner. Mad cows take beef off the menu in the UK or pasta strikes in Italy takes lasagne off the menu – they disrupt our menu routine.

Strange Attractor

The final type of attractor is well, strange. Strange attractors are the characteristic feature of chaotic systems. The describe open systems rather than closed ones. This is a good thing because it allows us to take into account all the complexity (the broader context) in which the three previously described closed systems operate.

A strange attractor limits the system to exhibit the self-similar, sort of like old repeating patterns, but because they are not totally closed other factors can influence the system and change things, sometimes dramatically. The system is in a constant flux between the stability of the closed systems and the complete break down of the systems into chaos – sometimes this is referred to as the edge of chaos.

You are a limited by a strange attractor. Over the years you have demonstrated remarkable self-similarity of appearance – to the point that it is likely that strangers could match up a photo of you when five years of age to a current picture (assuming you have gone lightly on the plastic surgery and avoided moving to Cheshire and going orange). However clearly your good adult self is also different to that five year old.

Strange attractors require us to embrace paradoxical thinking – the same, but different. Stable but unstable. Predictable (within severe limits) but unpredictable over time. When you plot out the patterns of a strange attractor you get a fractal pattern. Fractals are the graphical patterns that emerge from the operation of strange attractors.

The Strange Attractor operates when the system shows emergent stability over time, self-similarity, but also the possibility for radical non-linear change.

Now those last paragraphs were chock full of jargon or more positively some of the new language that can help us understand careers. As Stephen Fry points out in his The Ode less travelled “It is useful and pleasurable to have a special vocabulary for a special activity. Convention, tradition and precision suggest this in most fields of human endeavour..”

To link this to career behaviour consider the dizzying number of influences upon our career behaviour, people such as Lent, Brown and Hackett or Patton and McMahon have highlighted the multitudinous nature of these influences. Bright, Pryor, Wilkenfeld & Earl (2005) presented data from a sample of around 750 young adults that demonstrated they were influenced by everything from parents to geography to politicians and beyond. They were also very commonly influenced by chance events. A point that John Krumboltz has been making for a long time (e.g. Krumboltz, 1998).

In the Chaos Theory of Careers (CTC) we characterise individuals as complex systems subject to the influence of complex influences and chance events. However over time patterns emerge in our behaviour that are self-similar but also subject to change. Career trajectories/histories/stories are examples of such complex fractal patterns.

- Our careers are subject to chance events far more frequently than just about any theory other than CTC and Happenstance Learning Theory would suggest.

- Our careers are subject to non linear change – sometimes small steps have profound outcomes, and sometimes changing everything changes nothing.

- Our careers are unpredictable, with most people expressing a degree of surprise/delight or disappointment at where they ended up.

- Our careers are subject to continual change. Sometimes we experience slow shift (Bright, 2008) that results in us drifting off course without realising it, and sometimes our careers have dramatic (fast shifts) changes which completely turn our world upside down.

- We and therefore our careers take shape and exhibit self-similar patterns, trajectories, traits, narratives, preoccupations over time.

- We and therefore our careers are too complex to be easily captured and put into simple boxes, interest or personality codes.

- Perhaps more contentiously given the almost completely uncritical acceptance of narrative as our technique du jour, narrative too, represents an over-simplification of reality and is not capable alone of fully capturing the complexities of our careers. However it is more capable of capturing complexity than scores alone.

At this stage I need to add one more term to complete our tool kit to engage with our clients in a way that embraces complexity, and that is constructivism.

We are pattern makers, we can find connections and structure in almost any stimuli. The tools we use to make the constructions include numbers, circles, triangles, squares, boxes, lines, and stories. In this we we capture human behavioural patterns in test scores, we talk of putting people in boxes, pinpointing (a small circle), predicting (a line) or hearing their story.

The CTC has at it’s heart the idea of emergent patterns. In seeking to understand these exceedingly complex and ever changing patterns we all will construct meaning from our experiences of these patterns. However as Pryor and Bright (2003) pointed out this does not mean we adopt a radically socially constructivist stance, rather we adopt a realist – constructivist position – that reality exists beyond our perceptions of it, but we acknowledge that our experience of reality is influenced by our constructions we place upon it. I say more about this in the counselling section.

CTC and Counselling Techniques – lets end the war before we start.

The CTC demonstrates clearly the limitations of “traditional” ideas like fit between people and jobs, psychometrically measured interests, values and personality in trying to capture dynamic and complex patterns. Equally despite pointing out that narrative is limited too, this does not mean that narrative has no place in the CTC, it does.

Savickas (2005) described as an “epistemic war” has been going on either explicitly or implicitly between what could variously be designated the modernist, objectivist, positivist perspective and the post modernist subjectivist constructivist perspective.

The former approach focuses attention on assaying individuals’ characteristics (abilities, preferences and traits) and relating those to the requirements of various occupations. The better the fit the more suitable the occupation. The latter perspective focuses attention on discovering themes and purpose through narratives with the goal of creating a meaningful life incorporating work.

The Chaos Theory of Careers provides a theoretical method for resolving this conflict and ending the war. Bright and Pryor (2007) proposed that the positivist and the constructive perspectives actually correspond to the two dominant categories of characteristics of complex dynamical systems. Using the term “convergent” perspective to correspond to the positivist approach it was suggested that the focus was on the stable, identifiable, ongoing characteristics of individuals. This perspective seeks to identify “probable outcomes” based on past behaviour and knowledge.

The convergent perspective draws attention to the ordered patterns that are identifiable within complex dynamical systems as a basis for narrowing down (converging) options in order to make a satisfying and effective choice. The emergent perspective points to the susceptibility of change within complex dynamical systems. From instability interaction and forming new connections of influences within the system, new characteristics develop (emerge). For example from a convergent perspective someone making a decision is an individual evaluating skills and personality to match with an occupation. However, from an emergent perspective such an individual could be perceived as part of a complex network of influences mutually influencing one another out of which a sense of purpose emerges through which a congruent work context is constructed.

It still may appear that these two perspectives – the convergent and the emergent – remain as contradictory as the positivist and constructivist approaches. However this is exactly the kind of dichotomous thinking that views order and disorder as opposites when in fact in the Chaos Theory of Careers they are views as composites of complex dynamical systems.

Through the CTC it can be seen that the insights of both the convergent and emergent perspectives make a contribution to a further understanding of the individual’s personal story and self – concept on the one hand and on the other how such insights may correspond to a broader understanding of how society arranges work, reputation and the demonstration of abilities for work entry and performance on the other. There seems little point in knowing how your abilities and interests compare with other people (convergent perspective) if the utilization of such personal characteristics lacks meaning for you (emergent perspective). Conversely simply focusing all one’s attention on visualizing a fulfilling lifestyle incorporating work (emergent perspective) if that vision has no chance of actually being realized through the world of work suggests the need for objective occupational information (convergent perspective).

Finally, as Kitching (2008) points out in his critique of postmodernist thinking, the emphasis is firmly upon what we “know” about the world and ourselves, and has surprisingly little to say about how we “act” in the world. As Kitching puts it, “it privileges epistemology over ontology”. If all there is in the world are ones thoughts, then there is little point in acting, we can simply think our way through everything. However most counsellors will recognise the truth in the saying “nothing will be achieved if first all objections must be overcome”, very often the way to confront uncertainty and the fear commonly associated with it is to act. Consequently the CTC approach embraces the paradox of think before you act, but act before you think (Pryor & Bright, 2008). Action is emphasised in other approaches including Krumboltz’s Happenstance Learning theory and Young & Valach’s action theory.

Further Reading

The Factory Blog and the Careers in Theory Blog by David Winter

Link to a companion piece to this article providing a step by step guide to using the the Chaos Theory of Careers practically in Counselling on the Careers in Theory Blog

Books

Pryor, R. & Bright, J. The Chaos Theory of Careers. Routledge, New York. To be published January 2011. Contains an extended coverage of practical counselling strategies, tools and techniques as well as a review of the empirical evidence supporting the theory, and more.

Amundson, N. (2009). Active Engagement. 3rd Edition. Ergon Communications. Richmond:BC

Papers

Bright, Pryor, Chan, Rijanto. (2009). The dimensions of chance career episodes. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 75(1), 14-25.

Pryor, R.G.L. and Bright. J.E.H. (2009). Game as a career metaphor: A chaos theory career counselling application. British Journal of Counselling and Guidance. 37(1), 39-50.

Bright, J.E.H. & Pryor, R.G.L.. (2008). Shiftwork: A Chaos Theory Of Careers Agenda For Change In Career Counselling. Australian Journal of Career Development. 17(3), 63-72.

Pryor, R.G.L. & Bright, J.E.H. (2008). Archetypal narratives in career counselling. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance. 8(2), 71-82.

Pryor R.G.L., Amundson, N., & Bright, J. (2008). Possibilities and probabilities: the role of chaos theory. Career Development Quarterly 56 (4), 309-318.

Pryor, R.G.L. & Bright J.E.H. (2007). Applying chaos theory to careers: Attraction and attractors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71(3), 375-400.

Bright, J.E.H. & Pryor, R.G.L.. (2007). Chaotic Careers Assessment: how constructivist and psychometric techniques can be integrated into work and life decision making. Career Planning and Adult Development Journal, 23 (2), 30-45.

Pryor, R.G.L. & Bright, J.E.H. (2006). Counseling Chaos: Techniques for Practitioners. Journal of Employment Counseling. Vol 43(1) Mar 2006, 2-17

McKay, H., Bright J.E.H. & Pryor R.G.L. (2005) Finding order and direction from Chaos: a comparison of complexity career counseling and trait matching counselling. Journal of Employment Counseling. 42, (3) Sep 2005, 98-112

Davey, R., Bright, J.E.H., Pryor, R.G.L. & Levin, K. (2005). Of never quite knowing what I might be: chaotic counselling with university students. Australian Journal of Career Development, 14(2), 53-62.

Pryor, R.G.L. and Bright J.E.H. (2005). Chaos In Practice: Techniques for Career Counsellors. Australian Journal of Career Development, 14(1), 18-28.

Bright J.E.H. & Pryor R.G.L. (2005). The chaos theory of careers: a users guide. Career Development Quarterly. Vol 53(4) Jun 2005, 291-305

Pryor, R. G. L. & Bright, J. E. H. (2003). The chaos theory of careers. Australian Journal of Career Development, 12(2), 12-20.

Pryor, R. G. L. & Bright, J. E. H. (2003b). Order and chaos: a twenty-first century formulation of careers. Australian Journal of Psychology, 55(2), 121-128.

Savickas, M. L. (1997). The spirit in career counseling: Fostering self-completion through work. In D. Bloch and L. Richmond. (Eds.), Connections between spirit and work in career development: New approaches and practical perspectives. (pp. 3–26). Palo Alto, CA: Davies-Black Publishing.

Loader, T. (2009). Careers Collage: applying an Art therapy technique to career development in a secondary school setting. Australian Careers Practitioner. Summer, pp16-17.

Related Posts

Pingback: Tweets that mention A “twitter” -brief summary of the Chaos Theory of Careers. | The Factory -- Topsy.com

Pingback: Web-based Career Services - if you go down to the virtual woods today.. | The Factory

Pingback: Is the Chaos Theory of Careers doing Practitioners out of a job? | The Factory

Pingback: The imperfect career and a gift from Brené Brown | The Factory

Pingback: The Strange Strength of Vulnerability | The Factory

Pingback: Embracing Uncertainty in Life and Careers | The Factory